“I think one of the takeaways of the book is that success kind of is a moment in time,” Dominus tells Fortune. “The fact that people have ups and downs does not detract from the accomplishments of their ups. But it’s also a recognition that success is a very fleeting thing to some degree.”

Still, it’s the success of others—especially multiple-success families like that of the Wojcickis—that has intrigued the writer since her childhood. That’s when, as she describes in her book’s introduction, she began noticing in earnest the differences in how families operate behind closed doors.

“I saw in the home of childhood friends that the family culture was very much about enrichment and discussion and thinking on your feet and testing your wits,” she recalls, referring to a friend’s family whose father posed intricate questions of math and logic at the dinner table (while the only rule at her family’s table was to “clean our plate and chew with our mouths closed.”)

“I think that it just made me curious,” she says. “Would I be better at math if this was part of our family culture? …Would I just be smarter, better prepared, more confident, if I had grown up in that kind of environment?”

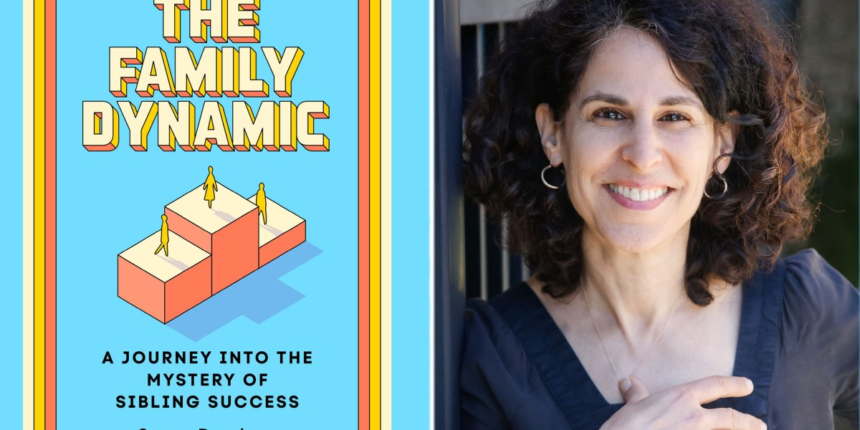

Those questions are at the heart of The Family Dynamic, which deep dives into the early family lives of high achievers including, among others, the Brontë sisters, the legendary lawyer-activist Holifield clan, the judge-and-activist sisters Mary and Janet Murguía, the Groffs (family of novelist Lauren Groff and her successful siblings), and the Wojcickis.

Though she labored over the book for 10 years—in between working full-time and raising her twin boys, now 18—her research began, informally, years earlier, as she devoured books about the early lives of families including the Kennedys and the Wright brothers.

“I just wanted to know what they were like as kids, and what their parents’ interaction was with them, and how they got along,” she said of the first-in-flight siblings.

Below, 4 lessons Dominus learned about success and its origins.

“It’s demanding. It can be self-absorbing. You can lose touch with the things you care about,” Dominus says of highly successful individuals. “Very many people get depressed the minute they’ve accomplished a goal that they’ve been fighting for their whole lives.”

By the end of her research, Dominus says, “I felt more keenly aware that success is fraught.”

Dominus writes about one pair of sisters in which one—the “energetic doer,” always striving for more—is forever frustrated with the other, who was “dreamy” It took until adulthood for the doer to recognize that her daydreaming sister—eventually a successful creative in the theater world—had her own kind of grit.

“There are so many people who I consider to be so successful who don’t have those classic credentials,” says Dominus. Recently asked to name the most successful person she knows, she said it was her child’s kindergarten teacher.

“She is, in some ways, the most admired person in town,” the writer says. “She’s the person who did so much for so many kids and made school a joy… Everyone would, like, sell their left arm to have her for their child’s kindergarten teacher. And I just think, wow—that’s somebody who has to go through life knowing her life has purpose.”

Dominus did find some common ground among those she interviewed—including a “tremendous spirit of optimism in every one of these families.” That optimism was at the foundation of family mottos used to motivate the children. Marilyn Holifield used to say, for example, “All things possible.” The mother of the Murgías sisters would say, “With God’s help, all things are possible.”

But the trick, she realized, is that “they had to believe it for their children to internalize it.” And these parents—resilient and successful themselves, often in spite of very difficult circumstances—really did believe that all things were possible.

“Patrick Brontë grew up in an extremely poor family in Ireland,” Dominus says. He attended Cambridge on scholarship, dealt with racism against the Irish at that time, and thrived. “His entire life experience was ‘all things possible.’ So why wouldn’t his daughters think: That’s right… We’re going to write some groundbreaking literature and blow everyone’s mind.”

Dominus adds that the “all things possible” motto is very different from what she heard in her own childhood. “I always joke that the only thing I remember my father saying was, ‘If something seems too good to be true, it probably is.’ Of course, here I am a journalist, extremely skeptical,” she says with a laugh. “But I think if my father had said things like, ‘Sky’s the limit,’ ‘All things possible,’ I might not have believed it.” Because he likely wouldn’t have, either.

Dominus tried a little of everything when it came to raising her twin boys—having them both play instruments, getting the New York Times actual newspaper delivered in order to leave it around for them to pick up, doing family readings of Julius Caesar aloud during the pandemic, for example. But she also made sure to get out of their way.

“To be honest, I can’t even make my boys make their bed in the morning,” she says. “I think it was more about what we put in front of them.”

Now, she says, the two boys could not be more different: One is the social chair of his fraternity at the huge University of Wisconsin, while his other attends a school of 400 where “they basically study ancient Greek and read Aristotle.” And, she adds, “we’ll never know: Were they reacting to each other, or did they just come out that way, and all the parenting in the world wasn’t going to make them more similar?”

That experience, coupled with all she learned from the families interviewed for her book, has led Dominus to a conclusion to the never-ending question: Is it nature or nature that has the most influence?

“I think two things,” she says. Nature—or talent—is important. But you must also have “an environment that encourages or recognizes that,” she says. In other words, one needs to also be nurtured.

“We know that there’s so much talent in this world that goes unrecognized because of where people live and what their opportunities are,” she says. “And if nature is going for you and nurture is going for you, then you have a much greater shot of making it big.”

But that’s not everything, she says. It also has a lot to do with luck.

“I think we also have to acknowledge that luck really does play a tremendous role in people’s lives. And there are some people who make their own luck, it’s true. But also there are people who do happen to be in the right place at the right time,” says Dominus. “I think people under-appreciate the role of luck in their lives.”

More on parenting: