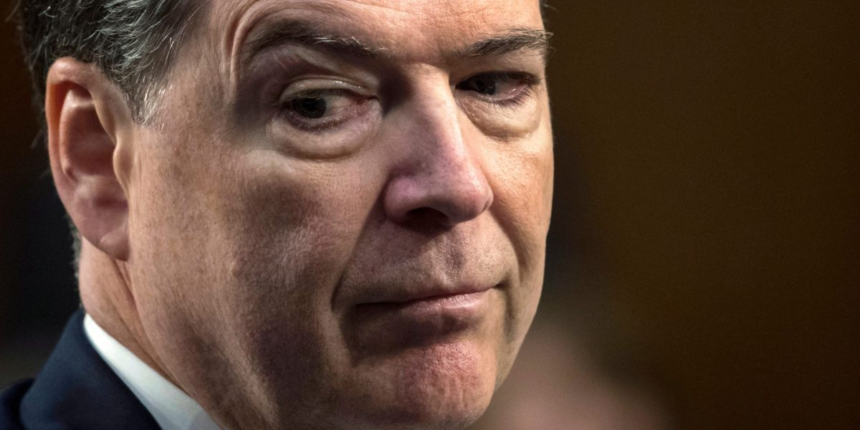

Halligan initially asked the grand jury to return a three-count indictment against Comey. But after the grand jurors rejected one of the proposed counts, Halligan secured a second two-count indictment that accused Comey of making a false statement and obstructing Congress. Comey has pleaded not guilty and denied any wrongdoing. The charges are related to sworn testimony about whether Comey had authorized an FBI colleague to serve as an anonymous source to the news media.

In a ruling Monday, U.S. Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick, also handling parts of the case, said he had reviewed a transcript of the grand jury proceedings and had questions about whether the full grand jury had reviewed the final two-count indictment that was returned.

The issue arose again on Wednesday when Nachmanoff, the trial judge, pressed the Justice Department about Fitzpatrick’s concerns. After conferring privately with Halligan, Tyler Lemons, a prosecutor in the case, acknowledged that the revised indictment was not shown to all of the grand jurors.

“I was not there, but that is my understanding, your honor,” Lemons told the judge.

Nachmanoff called Halligan to the podium and asked her who was in the courtroom when the final indictment was presented to a magistrate. She said only two grand jurors, including the foreperson, were there.

Comey lawyer Michael Dreeben said the government’s failure to present the final indictment to the entire grand jury is grounds for dismissing the case. He also argued that the statute of limitations for the charged crimes has elapsed without a valid indictment.

“That would be tantamount to a bar of further prosecution in this case,” Dreeben said.

Nachmanoff did not issue an immediate decision, saying “the issues are too weighty and too complex” for him to rule from the bench.

Dreeben separately argued that the prosecution was improperly vindictive and rooted in Trump’s quest for retribution, circumstances requiring a dismissal.

“The president’s use of the Department of Justice to bring a criminal prosecution against a vocal and prominent critic in order to punish and deter those who would speak out against him violates the Constitution,” Dreeben said,

Motions claiming vindictive prosecution are not often successful.

“If this is not a direction to prosecute,” Dreeben said in court, “I’d really be at a loss to say what is.”

Halligan secured an indictment of Comey days later as the statute of limitations on the case was about to expire.

“She did what she was told to do,” Dreeben said in court.

Presidents, he said, have other tools at their disposal to punish critics, but bringing the full weight of the Justice Department to bear is impermissible.

“The government cannot use power of criminal prosecutions to attempt to silence a critic in violation of the First Amendment,” he said.

Lemons, the Justice Department prosecutor, said Comey was indicted by a “properly constituted” grand jury because he broke the law, not because Trump ordered it.

“The defendant is not being put on trial for anything he said about the president,” Lemons said.

Lemons said nobody directed Halligan to prosecute Comey or seek his indictment.

“It was her decision and her decision only,” he added.

But Nachmanoff, the judge, noted that Trump appointed Halligan as acting U.S. attorney on Sept. 22, three days before she presented the case against Comey to the grand jury.

“What independent evaluation could she have done in that time period?” he asked Lemons.