Spencer said that he was thrilled when a summary of the U.S.-EU agreement released in August mentioned cork.

“It was a great day in our neighborhood,” said Spencer, a self-described “cork dork.”

Cork has other applications too. NASA and SpaceX have used it for thermal protection on rockets. Cork crumbles are also used as infill for sports fields and inserted into concrete on airport runways to help absorb the shock of plane landings.

But the effort evaporated when the war ended. The problem is that it takes 25 years for a cork tree to produce its first bark for harvesting, and the initial yield typically isn’t high quality. After that, it takes the tree about nine years to grow new bark.

Cork harvesting is also an extremely specialized skill, since cutting into a tree the wrong way could kill it. Cork harvesters are the highest paid agricultural workers in Europe, Spencer said.

Amorim, which exports cork to more than 100 countries, has more than 20 million cork trees spread over 700,000 hectares (1.7 million acres) of woodland.

On a recent day at Amorim’s Herdade de Rio Frio, a farm 40 kilometers (25 miles) southeast of Lisbon, crews zig-zagged across the thin, pale grass between scattered cork trees, kicking up dust.

The quiet woodland echoed with the gentle thud of the workers’ axes. They gently pierced the bark, feeling for the thickness of cork that could be peeled off without harming the trunk. The Portuguese have harvested cork this way for more than 200 years.

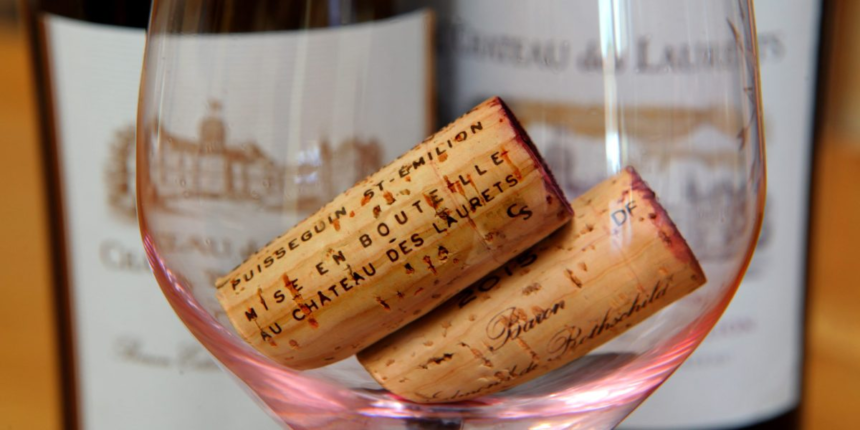

The tree bark came off in featherweight slabs that the workers, their hands black from the oaks’ natural tannins, tossed onto a flatbed truck. It would go to factories to be cut into strips and fed into a machine that punches out stoppers.

Cork’s sustainable harvesting process and its biodegradability are two reasons that many U.S. winemakers have returned to plugging bottles with it after experimenting with closures made of aluminum, plastic and glass. In 2010, 53% of premium U.S. wines used cork stoppers; by 2022, that had risen to 64.5%, according to the Natural Cork Council.

Cork taint, which gives wine a funky taste and is caused by a fungus in natural corks, was a big problem in the 1990s, and it pushed many vintners into aluminum screw caps and other closures, said Andrew Waterhouse, a chemist and director of the Robert Mondavi Institute of Wine and Food Science at the University of California, Davis.

“If you say, ‘Has this wine aged properly?,’ what you mean is, ‘Was it in a glass bottle with a cork seal in a cool cellar?’ Under any other conditions, it didn’t age the same,” Waterhouse said. “We’re always trapped by history.”

___

Dee-Ann Durbin reported from Detroit.