During the 15-minute meeting with Epstein, the bankers were quickly ushered into the financier’s in-house conference room, where they sought to communicate the seriousness of the allegations. “He lied about everything,” one of the bankers told Fortune under the condition of anonymity, owing to fear of reputational and professional retribution. Epstein insisted the new claims against him were bogus. Legal filings in an Epstein victim lawsuit against Deutsche Bank corroborate this account.

Deutsche Bank took him at his word, and continued to manage Epstein’s money until mid-2018, according to lawsuits from Epstein’s victims and Deutsche Bank’s shareholders.

“The bank regrets our historical connection with Jeffrey Epstein. We have cooperated with regulatory and law enforcement agencies regarding their investigations and have been transparent in addressing these matters in parallel. In recent years Deutsche Bank has made considerable investments in strengthening controls, including bolstering our anti-financial-crime processes through technology, training, and additional staff with dedicated expertise,” a Deutsche Bank spokesperson told Fortune.

“It’s not news that Epstein knew Donald Trump, because Donald Trump kicked Epstein out of his club for being a creep. Democrats, the media, and Fortune magazine knew about Epstein and his victims for years and did nothing to help them while President Trump was calling for transparency, and is now delivering on it with thousands of pages of documents,” White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson told Fortune. (Fortune is not involved in the Epstein case.)

This legislation would require the Justice Department to publicly release all unclassified records related to Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell within 30 days.

No one outside the Department of Justice knows what the unreleased files say, or whether they contain any information about Trump’s or Epstein’s dealings with the bank.

Discovery in the victims’ civil suits, however, was voluminous. Those documents continue to exist under a protective order and include financial statements, transaction records, and internal memos related to Epstein’s business at the bank. Owing to the nature of the settlement agreement, the full record from Deutsche Bank was never made public—but it has been preserved. If these documents are protected in the civil courts, almost certainly Department of Justice prosecutors had access to them.

One of the former Deutsche Bank executives who spoke with Fortune believes the sealed information on Epstein could help illuminate how he was able to fund his sex-trafficking operation using his network of accounts, including those at Deutsche Bank. If the remaining files are ever released more detail about Epstein’s banking may come out: “That looks like it would be true,” the source said.

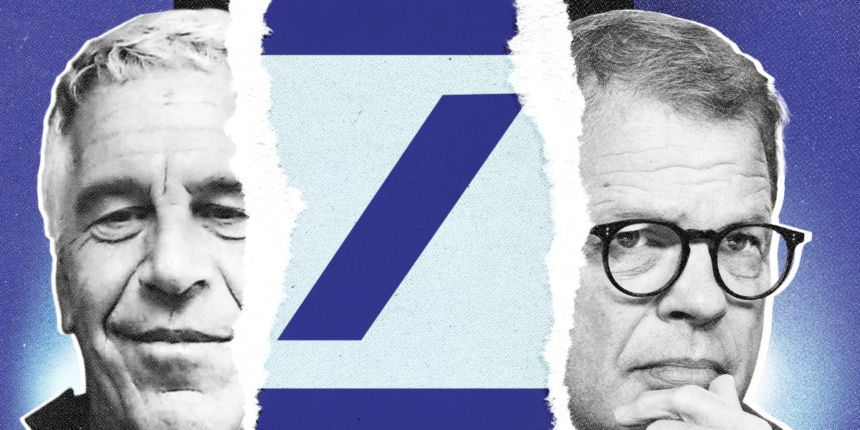

A raft of litigation related to Epstein, settled by the bank in 2020 and 2023, describes in detail Epstein’s relationship with the bank in the years leading up to his 2019 arrest. Fortune examined more than 400 pages of legal filings and spoke to experts on banking regulation and multiple sources directly involved with Epstein’s accounts at Deutsche Bank to examine why the bank is still haunted by him.

A legacy of risky business

Deutsche Bank is no stranger to paying a price for its business tactics.

Deutsche Bank denied wrongdoing in a statement to Fortune. “As disclosed in our Annual Report, the bank has been aware that five individuals have threatened to file claims in the U.K. in the context of this matter. Deutsche Bank considers all such claims to be entirely without merit and will defend itself against them robustly,” a Deutsche Bank spokesperson said, emphasizing that Sewing was not named in the latest London legal filing.

But the case spotlights the German lender’s culture of operating with a disregard for reputational risk.

Why Deutsche said yes to Epstein

To outsiders, the decision to court Epstein after his fall from grace seems baffling. But to experts, it fits a pattern. “Deutsche Bank has a long history of doing business with shady customers, and sometimes with practices that are outright misconduct,” Anat Admati, a Stanford finance professor who has written extensively on banking regulation and governance, told Fortune. “Often, there is very little downside for the bankers who bring in that business. The incentives are all tilted toward chasing profit, even if it means enabling bad actors.”

Competition among banks to match profits and return on equity with peers has long created a culture of risk escalation, especially for Deutsche Bank, according to Admati, which wants to compete with more prestigious U.S. giants like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase.

A spokesperson for Goldman declined Fortune’s request for comment. JPMorgan did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment.

Admati pointed to Deutsche Bank‘s culture of managerial pressures and bonus structures as drivers of high-risk behavior, namely its unrealistically high return-on-equity targets.

Throughout much of the early aughts, the German bank publicly set very high targets for return on equity ranging from 20% to 25%, Admati and coauthor Martin Hellwig explained in their book, The Bankers’ New Clothes. To meet those targets, especially when market conditions or interest rates made organic growth more difficult, managers were more inclined to take on additional risk that promised higher yields, the scholars argue. According to them, managers and traders at Deutsche Bank were also evaluated and compensated largely on short-term profit and annual ROE metrics. When these risky investments paid off in the short term, bonuses could be substantial. Ultimately, bankers at Deutsche Bank were incentivized to book large upfront profits even when long-term risk remained hidden, the pair say.

“Epstein fits into that picture of a bank that just didn’t have its internal controls entirely in order,” he said.

“Sometimes firms override what they hear from their legal and compliance people and proceed anyway for purely business reasons,” James Fanto, a Brooklyn Law School professor, told Fortune. “In Deutsche Bank’s case, competing against giants like JPMorgan, they may have felt pressure to take on clients that carried legal or reputational risk. And in many instances, the fines end up being treated as just the cost of doing business.”

Deutsche Bank did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment on the aforementioned claims or its past financial scandals.

Banking for Mr. Epstein

In total, Deutsche Bank’s relationship with Epstein cost the bank more than $350 million in settlements and fines, including penalties imposed by NYDFS in 2020. The $150 million fine was part of a larger agreement that covered several compliance failures. Throughout the NYDFS investigation, the regulator found that Deutsche Bank had “significant compliance failures” and had not properly monitored suspicious account activity for years, despite the “publicly available information concerning the circumstances surrounding Mr. Epstein’s earlier criminal misconduct.”

Deutsche Bank’s relationship with Jeffrey Epstein began in August 2013 when his former bank, JPMorgan, began distancing itself from him. In need of a bank willing to handle his complex financial operations despite his reputation, Epstein found that the German bank not only welcomed his business but would facilitate it for five more lucrative years, even as red flags emerged that his accounts were being used for potential illicit activities, NYDFS investigative findings outline.

Court filings from a 2023 $75 million class-action settlement with Epstein’s victims reveal how Deutsche Bank became what the complainants alleged was the financial backbone of Epstein’s criminal enterprise from 2013 to 2018.

The connection began through Paul Morris, a relationship manager who left JPMorgan to join Deutsche Bank in November 2012, according to NYDFS records and Epstein victim and Deutsche Bank shareholder civil complaints. Having previously serviced Epstein’s accounts at JPMorgan, Morris saw an opportunity. In spring 2013, he pitched Epstein to Deutsche Bank’s senior management as a client who could generate millions in revenue as well as leads for other lucrative clients, according to an email cited in one of the lawsuits against the bank. “Estimated flows of $100–300 [million] overtime (possibly more) w/ revenue of $2–4 million annually over time,” he wrote.

According to one of the former Deutsche Bank executives who spoke with Fortune and worked under Jain, the former CEO was a “business first, ask questions later, kind of guy.”

Deutsche Bank did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment on Jain’s tenure at the bank.

“At the time, Epstein was lying repeatedly to everybody”

By 2013, Epstein’s criminal history was well-documented and widely reported. The bank was aware that he had pleaded guilty in 2007 to soliciting prostitution from a minor, served 13 months in jail, and was a registered sex offender. Prior to officially accepting Epstein as a client, a junior relationship coordinator at Deutsche Bank even prepared a memorandum, according to NYDFS findings and legal filings from Epstein victim and shareholder lawsuits, detailing Epstein’s multitude of sexual abuse allegations, plea deal, prison sentence, and involvement in “17 out-of-court civil sex abuse settlements.” When the relationship required approval, one executive who spoke with Fortune said they raised concerns about doing business with Epstein.

“At the time, Epstein was lying repeatedly to everybody, was donating large sums of money to Harvard and MIT, was in the social circle in New York … So the view of him at the time was very different,” the source said. “But there was a lot of smoke, and with the smoke, I said, ‘I don’t know if it makes sense to have this relationship. I’m not comfortable approving anything like this.’ So I escalated it.”

Their superiors, NYDFS investigative findings and the source claim, decided to move forward with managing Epstein’s money.

“What we did know is that he had been prosecuted in Florida and had received a short sentence for a state crime,” a separate former bank executive with intimate knowledge of the Epstein account told Fortune. “So it was a little unusual to allow somebody who had been convicted of anything to be permitted as a client. But it didn’t shock me that they felt that the circumstances were not enough to reject him as a client.” Fortune agreed to give this source anonymity because of the toxicity of being linked to Epstein.

Morris did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment.

Compliance officers raised concerns regarding Epstein’s accounts, according to the 2020 NYDFS investigative report and both the shareholder and Epstein victim lawsuits, in 2015 by prompting the bank’s Americas Reputational Risk Committee to finally meet to discuss the relationship. The committee ultimately decided to continue the relationship but imposed three conditions designed to monitor Epstein’s activities more closely. These conditions, sources told attorneys in the Epstein victim civil suit and NYDFS investigators, were never communicated to the relationship managers who could have enforced them.

Employees raised several other concerns during Epstein’s time with the bank, but the risk committee repeatedly decided to retain him as a client, the victim lawsuit, shareholder suit, and NYDFS investigation allege. A former Deutsche Bank executive confirmed to Fortune that multiple reports were made during their tenure on the Epstein account, and still he was kept on as a client. But confidential witnesses told investigators that the risk committee members were “primarily business-side people, meaning they were interested solely in making money for the Bank,” according to depositions conducted by NYDFS and the shareholder lawsuit filing against the German lender.

One of the former bankers who spoke to Fortune confirmed that having “business-side” employees on the committee made the group less effective in making impartial decisions about risk. “You want somebody who has no skin in the game making a decision dispassionately about the reputational risk in the bank, and if they had commercial leaders on there, they’re simply not in a position to do that,” they said.

Deutsche Bank did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment on the aforementioned claims.

The “Butterfly Trust”

The trust named three individuals as alleged participants and coconspirators in Epstein’s sex-trafficking operations, according to documents filed in the criminal trial of Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s 2007 Florida conviction, and several civil suits relating to Epstein’s operation. Given that none of these women have been charged criminally, Fortune will not disclose their names.

Between 2014 and 2018, Epstein used the trust to send over 120 wire transfers totaling $2.65 million to its various beneficiaries, according to the NYDFS investigative findings and the class-action complaint filed by Epstein victims. The trust made regular payments to the three identified coconspirators and women with “Eastern European surnames,” ostensibly for “hotel expenses, tuition, and rent.”

From 2013 to 2017, Epstein’s attorney made 97 withdrawals totaling over $800,000 in cash from Deutsche Bank’s Park Avenue branch. These withdrawals occurred around twice monthly each for exactly $7,500—the bank’s limit for third-party withdrawals. The regulatory investigation and the civil suits both claimed the money was for travel, tipping, and expenses.

One of the executives who spoke with Fortune described these large cash withdrawals as a “clear red flag” and a sign of “layering,” a process where illicit funds are complicated through a series of financial transactions to obscure their illegal origin.

These transactions, the victims’ lawsuit alleged, “furthered his sex abuse and the sex-trafficking venture, including funds paying directly for coercive and commercial sex acts, funds paid to professionals for carrying out illegal acts for the operation of the sex-trafficking venture.”

Deutsche Bank did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment on the aforementioned allegations.

Deutsche pulls the plug

Deutsche Bank’s relationship with Epstein finally ended on Dec. 21, 2018, when the bank informed him it would no longer service his accounts. The timing came months before his final arrest in July 2019.

As for the managers and traders primarily responsible for continuing Epstein’s business at Deutsche Bank, they appear to be unscathed. They continue to hold prestigious positions on Wall Street.

A former Deutsche Bank executive who spoke with Fortune anonymously still believes the bank acted properly and took concerns seriously. The exec expressed remarkably few regrets over a chapter that was, by any measure, catastrophic for the bank and the women Epstein victimized.

“All the information we could pull together on him was put before the general counsel and the head of compliance of the bank, and in their judgment, it was also okay to proceed,” the source said, a claim substantiated by NYDFS findings. “So do I regret how that was handled? No, I think that was exactly how it was meant to be handled. It’s just that we came to what turned out to be the wrong conclusion.”

This former executive’s sentiments were not shared by their ex-colleague who also spoke with Fortune anonymously.

“Culturally, I think Deutsche was broken. I think incentives were misaligned, and then I think that the bank didn’t have the proper controls to monitor everything it was doing, and that was a consistent theme across lots of different areas,” they said.

In their opinion, the bank hasn’t adequately compensated Epstein’s victims.

“I find everything he did reprehensible, in every way disgusting, and so in hindsight, I wish that the bank never would have adopted him as a client,” they said. “A $75 million settlement doesn’t sound like enough.”