Nextdoor, the social media site that aims to create connections among neighbors, is trying to shake off an uneven past and a nagging sense it is being underutilized. How? It is turning to professional journalists for help.

The company announced a partnership Tuesday with more than 3,500 local news providers who will regularly contribute material to the app. As part of a redesign, it is also expanding its ability to alert users about bad weather, power outages and other dangers, along with using AI to improve recommendations for restaurants, services and local points of interest.

“There should be enough value that we are creating for neighbors that they feel like they need to open up Nextdoor every single day,” said Nirav Tolia, the company’s co-founder and CEO. “And that isn’t the case today.”

The potential for Nextdoor to help itself and journalists at the same time is most intriguing.

Nextdoor is carrying portions of local news stories from providers in the area where the user lives. If people want to learn more, a link to the news site is included. At launch, Nextdoor says it has more than 50,000 news stories available, representing just over three-quarters of the app’s “neighborhoods.”

Into this tumult came an app with a promising premise and infrastructure, perhaps a template for local news of the future. Its users — Nextdoor likes to call them “neighbors” — were organized into more than 200,000 distinct neighborhoods, with the ability to start conversations once shared over back fences: Do you know a reliable babysitter? What’s that building going up down the street? Who serves the best burger?

Yet Nextdoor’s developers knew technology, not the news business. They didn’t see a role for professional journalists at the outset.

“We thought in our early days that neighbors would take over, almost as citizen journalists or local reporters,” Tolia said. “I think we’ve come to the conclusion that neighbors can only do so much.”

Even worse, the site became a magnet for racists and cranks, the kind of neighbors you try to avoid. Nextdoor became so filled with suspicion — why is a person of a different color or nationality walking down the street? — that its moderators had to spend considerable time rooting out racist posts and changing rules to prevent them.

For some users, the negatives outweighed the positives.

“Nextdoor has been a valuable resource for my family,” Ralinda Harvey Smith, a woman from Santa Monica, Calif., wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2020. “I found a nanny share for my kids on Nextdoor. When I posted looking for a mechanic to replace my car headlight, a neighbor offered to change it free of charge. When the pandemic struck and disinfectant wipes were impossible to come by, a woman on Nextdoor DM’d me offering to leave some on her porch.”

“Yet I’ve long seen remnants of racism across the site that have left me with a bad feeling not only about the app, but the city I love,” Smith wrote. That made her log on less frequently.

Whatever the reasons, enough users consider Nextdoor inessential that its leaders were compelled to make the changes being announced now. The site has 100 million registered users, but only about 25 million are on the site at least once a week, Tolia said. Nextdoor, which went public in 2021 to attract a new round of financing, wants to see them more often.

Nextdoor hired a former executive at The New York Times, Georg Petschnigg, as its chief design officer to oversee the changes.

The company said its surveys found users wanted to know more about what was going on in their communities beyond the utilitarian information. Other social networks are similarly bringing in more outside material, Tolia said. “When you rely on user-generated content, it’s kind of unpredictable in terms of quality, timeliness and relevance,” he said.

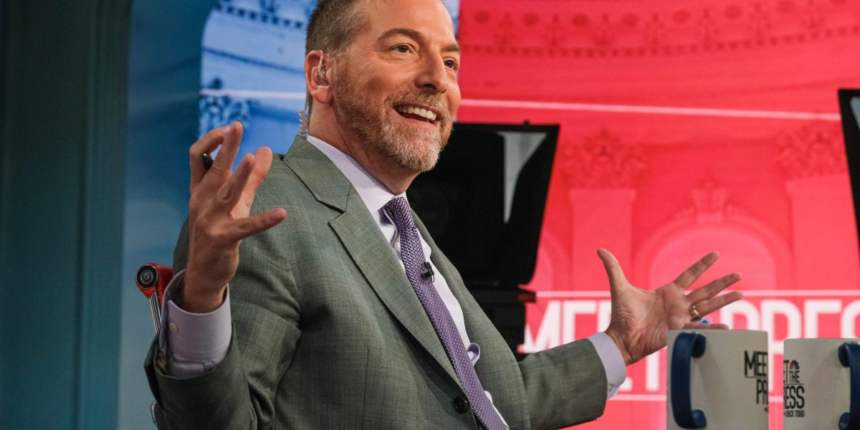

He is waiting to see if Nextdoor has a real commitment to news or just to reaching more eyeballs.

“It’s an opportunity to do the one thing that Facebook could have done but chose not to,” Todd said. “You don’t want this to go down the road of just trying to get traffic for traffic’s sake, because that’s what happened to Facebook after it went public.”

The irony of engaging with professional journalists isn’t lost.

Several of its participating news organizations are joining with Nextdoor, and “my hope is that our members see significant benefits from it,” Cholke said.

The local news industry continues to suffer from the same problems that have led to its downfall the past two decades: a dwindling number of readers and advertisers. An offhand comment by Tolia — about how people used to pick up “a piece of dead tree” from their driveways to get their news — speaks to fading prospects.

“If Nextdoor is another vessel to get readers to news sites, and local news sites in particular, it would come at a real moment of vulnerability for local news organizations and would be a real opportunity,” said Franklin, whose worry is that relying on third parties is unpredictable.

“I feel like media is in a state of evolution and there’s no playbook,” Schneps said. “My goal is to get our content in front of as many people as possible. I’m more than happy to be the guinea pig” for Nextdoor, he said.

An industry — and a company — both need help. Maybe they can help each other.